Amid all the hype of high democratic standards, fundamental human rights and liberties, The Economist, a popular British magazine, published an editorial and openly called on the Turkish electorate to vote against the Justice and Development Party (AK Party), pejoratively dubbing President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan “the Sultan.” Given the line of heavily biased journalism followed by mainstream international media outlets such as CNN, BBC and Deutche Welle over the course of recent months, such undiplomatic political propagation by The Economist is not surprising at all. In a typically neocolonial manner, the international media community seem to have committed themselves to “teaching the truth” to the Turkish electorate. They are somehow convinced that the AK Party under the watchful eyes of President Erdoğan is taking the country to the brink of a dictatorship and if only the country could get out of his grasp, we, Turks, might get a chance to enjoy real democracy. Perhaps we need to thank them for all their close interest in our democratization drive, but seriously question the simple and superficial answers that such an approach offers to our deep-seated democratization problems.

In fact, the complex relationship between democratization, economic development and political stability is highly contested in literature. Political history is full of examples of rapid economic development achieved in the absence of democratic institutions (South Korea, China), or stability was understood as the perfect functioning of key bureaucratic institutions, rather than electoral politics (Japan and Italy). Phrases such as “politicians reign, but bureaucrats rule” were developed for such national systems in which robust institutions maintained a sense of direction and continuity in macro-level national policies, leaving aside the vagaries and conflicts of party politics.

One crucial caveat to emphasize is that, despite crucial regulatory and institutional reforms over the course of the last decade, Turkey still does not represent one of those national systems. Therefore, effective political leadership and relative stability in electoral politics is desperately required to enable both the progress of structural reforms and a productive public-private synergy. The strong figure of Erdoğan as the leader of the AK Party and the government provided that comfort to both the Turkish electorate and the international financial-diplomatic community over the course of the last decade, so that long-term projects of socio-economic development, structural transformation and democratization could be achieved with relative ease.

Erdoğan has always been a sharp, undiplomatic and direct politician. In fact, it was exactly his peculiar political style that spread confidence among the Turkish electorate and Turkey’s international partners for long-term democratic stability. However, following the Gezi movement, The Dec. 17 and Dec. 25 incidents, and ensuing struggle against the Gülenists, the domestic and international atmosphere has been dominated by a media bombardment accusing Erdoğan of being responsible for all the country’s troubles. Despite lingering problems in Turkey’s democratization drive, this air of stigmatizing Erdoğan as a de facto “persona non grata” could well be conceptualized as a smokescreen designed to get rid of the strongest political actor representing stability so that the country could easily be incorporated into various international projections.

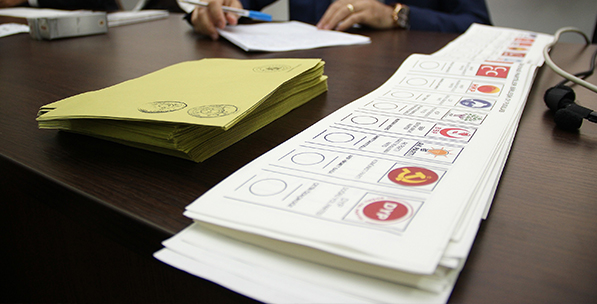

As the electorate goes the polls for a critical repeat election on Nov. 1, Turkey is longing for the virtuous circle of political and economic stability it was used to between 2002 and 2015. The failure of the AK Party to form a single party government after the June 7 elections created a heavier than expected national burden and triggered serious concerns for economic and political stability, which might have a negative impact on inflows of foreign investment and endanger some of the accomplishments of the last decade. The political impasse since the June 7 general elections; the reluctance of the main political parties to engage in rational coalition negotiations; the collapse of the resolution process; explosion of violence through the PKK and Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) attacks; and escalation of the Syrian civil war on Turkey’s doorstep displayed the critical importance of a strong and democratic government. Restoring “democratic stability” is key for Turkey, a country that suffered dreadfully in the past under the strain of military-backed efforts at restoring stability.

[Daily Sabah, October 30, 2015]

In this article

- Economy

- Opinion

- 2002

- 2015

- BBC

- China

- Civil War

- Daily Sabah

- Economy

- Election

- Elections

- Europe

- Global Actors | Local Actors

- Human Rights

- Iraq

- Islam

- Islamic

- Istanbul

- Italy

- Kurdistan Workers' Party Terrorist Organization (PKK)

- May 28-August 20 2013 The Gezi Park Protests

- Middle East

- Persona Non Grata

- PKK - YPG - SDF - PYD - YPJ - SDG - HBDH - HPG - KCK - PJAK - TAK - YBŞ

- Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

- Republic of Korea

- Syria

- Syrian Civil War

- Syrian Conflict

- Syrian Crisis

- taksim

- Terror

- The President of the Republic of Türkiye

- Turkish President

- Türkiye's Justice and Development Party | AK Party (AK Parti)