As we approach the completion of the first two decades of the 21st century, the enigmatic and puzzling term of “development” somehow manages to keep its attraction and grandiosity across the globe. Especially for the “developing countries” or “emerging economies,” it is one of the key components of national systems of self-perception and positioning in the global pecking order through the dynamic international division of labor. Socioeconomic development, developmental capacity, developmental dynamism and effectiveness are all eye-catching terms widely used by policy makers, private actors and civil society representatives alike. But the real substance of the notion of “development” has been in constant flux in line with conjectural changes, and has witnessed constant redefinition over the course of the last century. Therefore, it is not surprising to see various attempts for redefinition during our times as well.

Historically, development has more often not been defined as a state-centric concept on the basis of rapid industrialization and structural transformation, denoting profound change from agrarian to industrial social formations. Ever since the experiences of the second generation late industrializers of the 19th century, such as Germany and the U.S., humanity has been faced with a development issue, frequently conceptualized with reference to catching-up with the pioneering nations. Mercantilism, economic nationalism and protectionism all accompanied various conceptions of development in different historical epochs. For most of the post-war period, development was understood as a function of widespread industrialization under intense state interventionism, be it through European welfare states, East Asian developmental states or Latin American desarrolista states.

But with the mushrooming of multinational corporations and transnational civil society movements in the process of economic globalization, the widespread perception of development went through a radical transformation. Novel theoretical approaches such as “endogenous growth theory” and “competitive advantage of nations” facilitated a reformulation concentrating on the relative capacities of societies to innovate new technical and organizational means of wealth creation, instead of conventional methods of centrally planned state interventionism. This inclusive approach necessitated a focus on interactions between institutional formations in state bureaucracy, universities and research institutions, private sector actors and conglomerates, as well as, in political movements and civil society organizations. In the same line, the cumulative approach to development, which conceived improvements in national gross domestic product (GDP) and industrial production capacity gave way to a more organic and individualistic notion, which stresses the ability to form international linkages and improve average life standards of ordinary citizens in an environmentally friendly manner. As such, “human development,” as measured by the human development index, and “sustainable development,” as measured by the environmental impact of economic activities, gradually replaced the conventional GDP per capita, or output based measures.

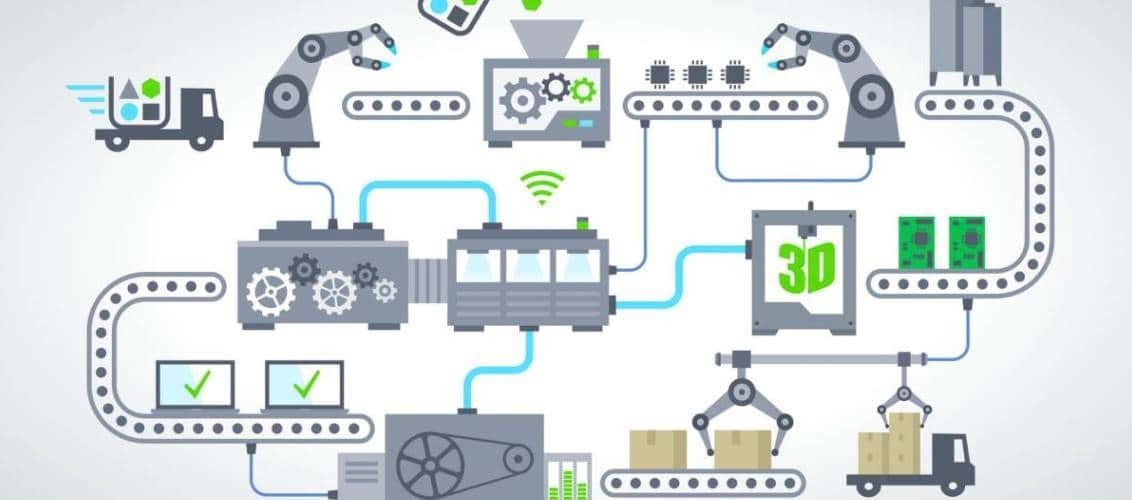

The infinite evolution of the term development continues along with the rapid advancement of technological know-how on the eve of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. As we witness the ever-closer integration of manufacturing and digital technologies, along with intensifying international competition, access to state-of the-art technology and fragmented processes of production also emerges as an element of development. Meanwhile, the increasing pace of technological progress and its highly uneven character creates new digital and technological divides among societies and redefines the main parameters of the international division of labor. Therefore, the intimate relationship between human welfare and the capacity to adapt to changes in digital and manufacturing technologies has become a direct concern for development debates.

But more importantly, an updated notion of development should embrace a global outlook and focus on structural imbalances in the world’s economy and distributional inequalities that impose acute poverty to certain societies. Normally, the category of least developed countries (LDC) should be an eliminated category in the long-term through the concerted efforts of better-off nations and international assistance bodies, rather than a neo-colonial portrayal propelling helplessness.

I welcome the holy month of Ramadan and hope that it brings peace and prosperity for the Muslim world and humanity.

[Daily Sabah, May 27, 2017]