The Syrian civil war has always had great potential to worsen any day. Since May 2019, the Bashar Assad regime has been pummeling the Syrian opposition’s last holdout in the northwestern province of Idlib. The potential for a worsening crisis reared its head when the regime attacked Turkish forces, killing seven Turkish soldiers and a Turkish military staff person. This undeclared war of sorts stopped short of heating up and instead shifted into a diplomatic row between the two guarantors of the Sochi agreement, Turkey and Russia. Ankara’s retaliation for the Assad regime’s attack, including “neutralizing” 76 regime soldiers, and regime forces entering into Saraqib, threatening more Turkish observatory posts, will no doubt spark a new phase of hostilities in Idlib.

Turkey and Russia agreed in late 2017 to work together to address the intensifying humanitarian crisis in Syria. As part of their cooperation, Russian and Turkish troops would enforce new demilitarized zones in Idlib in northwest Syria, Aleppo, Eastern Ghouta and Douma. Soon after the cooperation agreement, Syrian regime forces recaptured almost all of these areas with the exception of Idlib.

A subsequent agreement in September 2018 in Sochi, Russia, marked the greatest success of Russia and Turkey’s cooperation in Syria. The Sochi agreement established a cease-fire and a buffer zone. Those achievements held until recently, when the Syrian regime, buoyed by Russian support and military victory in other parts of Syria, began unscrupulously violating the agreement.

It is no secret that Assad wants to retake full control of Idlib as well as the M4 and M5 highways in order to connect Latakia, Aleppo and Damascus; however, under the Idlib cease-fire agreement, these roads are controlled by multiple forces. Whereas taking control of Saraqib would make it easier to control the highways, it would put Turkey’s observation posts south of the town at great risk. Ankara has constantly called on Assad to withdraw his forces back to the south in a rejection of his attempt to reclaim the de-escalation zone’s borders.

Any violation at this point would mean failure for the Syrian opposition, the tragic destruction of a safe zone for civilians who have a vague and uncertain future in the event that the regime recaptures the province and a new wave of refugees streaming to the Turkish border. It would also spell failure for both the Astana and Sochi processes. This is why this situation is so crucial for Turkey.

Idlib, as the opposition forces’ last stronghold, also has a symbolic meaning in peace talks in Geneva: Whoever controls Idlib will obviously have a big influence on the last word on the future of Syria. Idlib is of great importance for the Assad regime, as well, as it would strengthen his hand at the Geneva talks at a time when the regime is taking on the insane risk of confronting Turkish forces in open warfare on the ground for the first time since the beginning of the civil war. Obviously, this would be fatal for the Sochi agreement.

Strictly speaking, the outcome of the Syrian regime attacks in Idlib is a matter of life or death for the opposition’s role at the Geneva talks. The opposition will fight to the end to try to avoid weakening its position during its last chance at talks on Idlib.

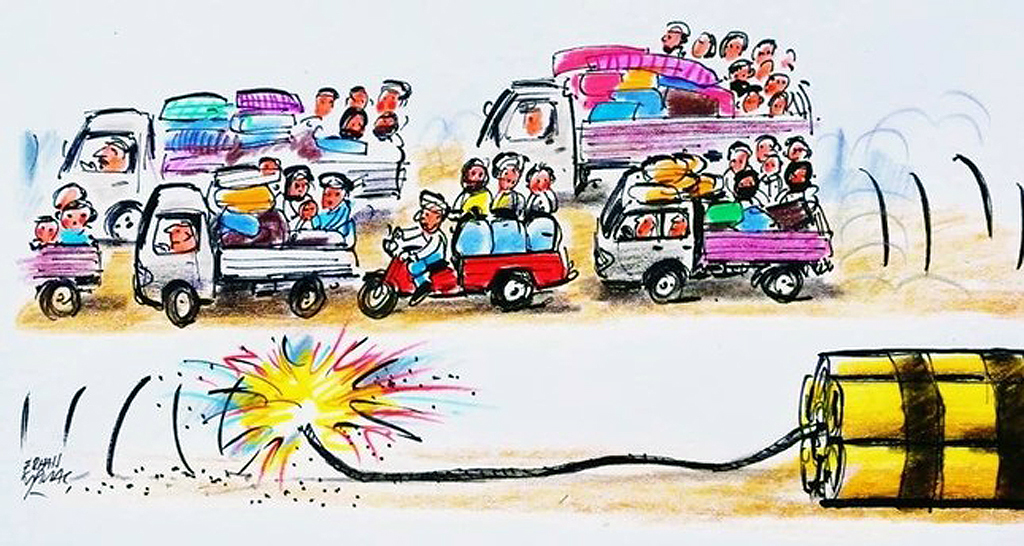

Idlib has a population of 4 million people, and persistent regime assaults there could drive a 1 million of them toward relative safety near the Turkish border. A new wave of refugees to the Cilvegözü border gate is Ankara’s biggest concern now. If the Assad regime violates the de-escalation zone and launches more attacks on civilian areas, Idlib will experience more human tragedies.

Since 2015, Ankara has been calling for de-escalation zones, safe zones or no-fly zones for refugees along its 911-kilometer border with Syria in response to the economic and political burden of hosting nearly 4 million Syrian refugees who have entered the country over the past five years. Ankara has reached its administrative and institutional capacity to accommodate this many refugees and as such, wants to prevent a possible new regional conflict that could cause more refugees to try to enter Turkey.

Ankara has proposed the creation of a safe zone in northern Idlib, as well as to build small houses south of the Turkish border, within an area 30 kilometers to 35 kilometers deep into Syrian territory. It is asking for support from the international community do be able to do this.

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said last Monday that EU countries and the U.S. have concerns about the humanitarian problems Idlib but have failed to take any concrete actions to solve them. Even though U.S. special envoy for Syria James Jeffrey said the violence in Idlib raises the specter of an international crisis and U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo condemned the Syrian government’s attacks in Idlib, reconfirming his country’s support for Turkey, concerns have materialized only into words, without action, and the EU has maintained its silence.

For the past two years, the Syrian civil war has been a multi-level game mostly between Russia and Turkey. The relationship between the two players is tested each and every time regime forces create a new situation on the ground. After the attack by Syrian regime forces last Monday, each side declared it had no intention of escalating the conflict and pursued diplomatic efforts to cool down the situation through ongoing dialogue between Erdoğan and Russian President Vladimir Putin. However, another inevitable aspect of this dialogue is that both Turkey and Russia should attempt to formulate a new process to navigate through the existing situation in Idlib. Both countries seem not to be changing their positions yet. To get there, the first thing they must do to drive this dialogue is to rebuild the trust between the countries, which was shattered when Russian Defense Minister Sergey Shoygu claimed that “Turkish military units made movements inside Idlib without warning” after Syrian regime forces killed seven Turkish soldiers and a civilian. Ankara firmly denied the assertion, saying that Moscow was informed of the Turkish military movements.

Turkey and Russia share very important initiatives, such as the construction and operation of the Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant, the S-400 missiles system agreement and the TurkStream pipeline projects, all of which make Russian-Turkish relations anything but a black and white issue.

As mentioned before, setting aside all conflicting interests, the only functional cooperation in Syria over the past two years has been between Turkey and Russia, particularly after the U.S.’ failure to keep its promises to its NATO ally. The dialogue between Ankara and Moscow is all that is left, and it must continue for Syria’s sake. However, if the Syrian regime persists in attacking Turkey’s observation posts, Ankara will not shy away from retaliating with military force. As a result, the conflict will be resolved on the ground instead of at the table. Drawing a new road map for resolving the conflict peacefully seems to be the only solution to the broken Sochi agreement and unobserved cease-fire in Idlib.

[Daily Sabah, 8 February 2020]

In this article

- Opinion

- Cease-fire | Ceasefire

- Daily Sabah

- European Union (EU)

- Humanitarian Crisis

- Idlib

- NATO

- NATO Ally

- Opposition

- Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

- Russia

- Syria

- Syrian Civil War

- Syrian Conflict

- Syrian Opposition

- Syrian Peace Process

- Turkish-Russian Relations

- Türkiye-Russia Relations

- U.S. Secretary of State

- United Nations Security Council (UNSC)