The political debate rages on in Turkey, although the National Assembly is still in summer recess. The discussions at the Istanbul Municipal Council’s September meeting focused on much more than local issues. In addition to the “waste of public funds” and municipal support for certain charities, the council’s members had heated arguments about national matters – the 1980 coup, the fight against terrorism, the Gezi Park revolts, the July 2016 coup attempt, the appointment of independent trustees to some mayoral posts, the dismissal of public officials, and a court ruling against the Republican People’s Party (CHP) politician Canan Kaftancıoğlu. In any other country, the municipal council’s agenda would seem overblown here. For Turks, it looks pretty ordinary. After all, the Turkish people have gotten used to the over-politicization of local and everyday issues since the Gezi Park revolts. It would take many volumes of thick books to capture all the polemics and accusations that politicians have made since 2013.

Still, there is something new lurking below the surface of today’s intense political debate. The July 23 municipal election triggered a notable psychological change.

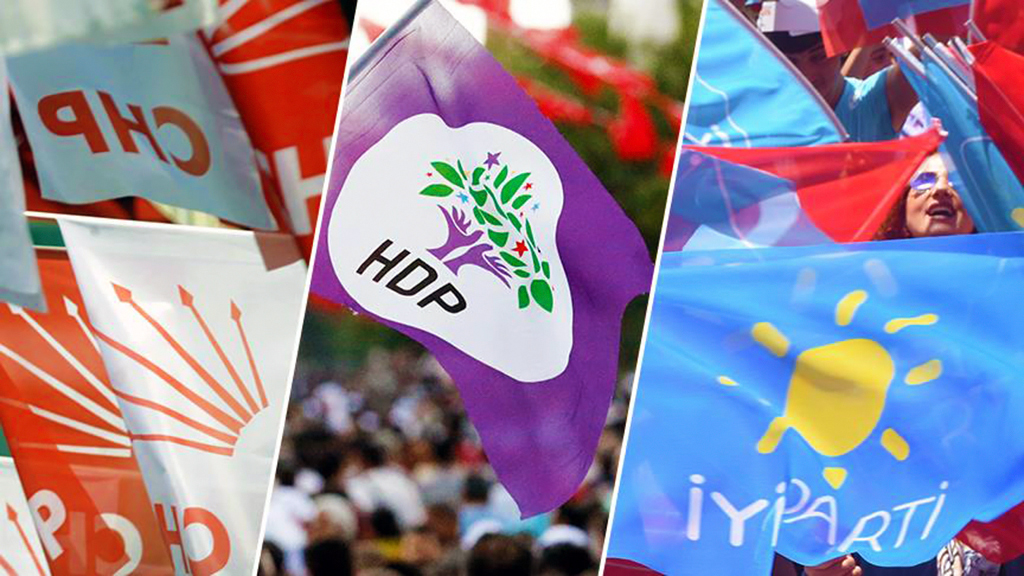

Despite still paying lip service to reconciliation, Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu fired thousands of municipal employees overnight. At the same time, his administration launched a crusade against charitable foundations offering free housing to low-income students. İmamoğlu is expected to replace those workers with members of the HDP and other allies of his party – just as he leased 997 new cars, while displaying 730 municipal vehicles as proof of the misuse of public funds. İmamoğlu’s brand of politics rests on the assumption that the things coming out of his mouth do not necessarily have to be true – which is also what he did on the campaign trail. It seems that Istanbul’s mayor finds comfort in the fact that telling lies did not cost him votes in the election. Perhaps İmamoğlu believes in the power of manipulation on social media. Or he takes for granted the support of voters who just want to remove the Justice and Development Party (AK Party) from power.

In my view, the biggest challenge facing İmamoğlu today is his love for national politics. Istanbul’s mayor will never stop trying to make a name for himself nationally. For a local politician who spends an unusual amount of time on vacation, that is a risky endeavor. Many voters already feel that İmamoğlu would be wise to focus on his job. His recent visit to HDP politicians in Diyarbakır, for example, sent shock waves through the CHP’s own nationalist base. The AK Party, in turn, is learning to speak the language of opposition at the local level. Having come to power just one year after its establishment, Turkey’s ruling party is relatively inexperienced in this area – even on a smaller scale. In Istanbul, local AK Party officials are trying to develop new rhetoric encapsulating the plight of municipal workers and to respond to allegations of “waste.”

In this article

- Opinion

- Daily Sabah

- Ekrem Imamoğlu

- Fight Against Terror

- Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality Mayor

- May 28-August 20 2013 The Gezi Park Protests

- Mothers from Diyarbakır

- Opposition

- September 11 2001 Attacks | 9/11

- Türkiye's Good Party (IP)

- Türkiye's Justice and Development Party | AK Party (AK Parti)

- Türkiye's Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP)

- Türkiye's Republican People's Party (CHP)