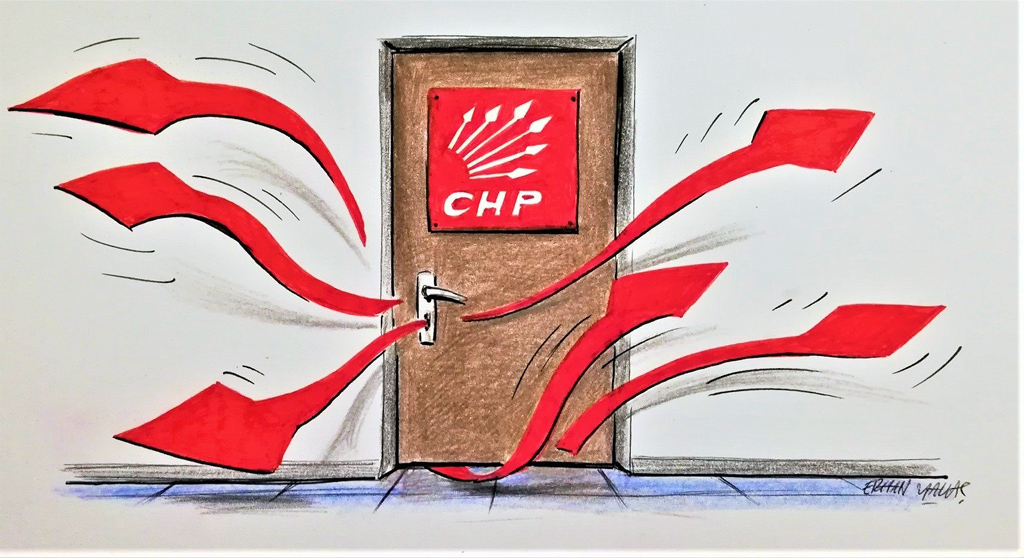

The main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) made headlines again, as three parliamentarians resigned and Muharrem Ince, the CHP’s presidential candidate in the 2018 election, is preparing to launch his own movement. CHP Deputy Özgür Özel, the minority whip, blamed these developments on President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, but the problem is more complex and deeply rooted. CHP Chairman Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu’s policy of stripping his party of ideology and identity, in an attempt to unite the opposition, appears to have hit a dead end.

One of those former CHP parliamentarians thus accused the main opposition’s leadership of begging foreigners for democracy, refusing to mention Turkey’s founding leader Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, conspiring against the intraparty opposition, being glued to their offices, placing their hopes in former President Abdullah Gül and similar politicians, and collaborating with the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP).

Faik Öztrak, the CHP spokesperson, may have dismissed those strong accusations as “allegations forged with the People’s Alliance’s words just as we are heading to victory.” But the crisis that plagues the main opposition party cannot be concealed that way.

Kılıçdaroğlu’s sole purpose is to create an embodiment of anti-Erdoğanism. In other words, he wants to draw a line between “advocates of democracy” and “proponents of authoritarianism” to unite the opposition around his plan to establish “an augmented parliamentary system.” The main opposition leader thus wants to accuse the ruling party of fueling polarization, whilst consolidating his own base.

For the record, the CHP chairman did get some results by sticking to that game plan. In 2019, the main opposition party secured the support of the Good Party (IP) and the HDP to win mayoral races in Istanbul and Ankara. Kılıçdaroğlu wants to do the same thing in 2023. Hence his use of radical phrases like “the militant and so-called president” and his push for early elections. He believes that polarization serves his party’s interests, but that strategy isn’t working anymore.

Although Kılıçdaroğlu rules the main opposition with an iron fist, he seems unable to keep the various intraparty groups together. The idea that the CHP could win the next election, which Öztrak noted, fuels competition over power, jobs, financial resources and political identity among its elite.

Ironically, the party’s success in the 2019 municipal elections appears to fuel hope and sows discord. Some CHP members feel that losing their ideology and identity is the price.

That’s why Ince’s critique – that there is no room left for Atatürk within the main opposition party — stands to present a serious challenge for the CHP chairman.

Loss of identity

To be clear, I am not talking about the loss of voters exclusively. The establishment of new political parties will highlight the CHP’s loss of identity and political platform. Self-criticism, which was quashed out of fear that it would strengthen the ruling party, will finally see the light of day.

The “neighborhood pressure,” as they say, no longer works. Former CHP members will target the main opposition party, just as the ruling Justice and Development Party’s (AK Party) former officials use the CHP’s arguments to attack the government.

Obviously, an increasingly fragmented opposition will contribute to Turkey’s culture of democracy by criticizing itself. As such, anti-Erdoğanism is no longer enough to keep the opposition together.

For the last decade, anti-Erdoğanism has been the bread and butter of opponents at home and abroad. The downside of that brand of politics is its reactionary nature and that it suppresses the debate among opposition movements. Ironically, uniting around anti-Erdoğanism neither wins over new voters nor resolves identity crises.

Therefore, some ambiguous proposal to restore the parliamentary system won’t be enough to serve as powerful glue. At the end of the day, the CHP won’t ever be able to tackle the “Kurdish question” despite its preparations.

Again, the constant messaging about early elections won’t make the opposition’s ideological disagreements go away. The fight against terrorism, foreign policy, the HDP’s marginalization and nationalism will continue to inform voter behavior.

Anti-Erdoğanism and polarization no longer provide the kind of comfort that they offered to the opposition for years. The ruling party, in turn, still has the initiative when it comes to developing policy. The main opposition party, by contrast, feels the pressure of failing to devise policy, losing its ideology and suppressing its identity to keep its fragile alliances in place.

Even secularism, the sole remnant of the CHP’s six arrows, has been downplayed. I am not even sure whether Kemalism means to the CHP leadership anything more than claiming Atatürk – a shared symbol of all parties.

The opposition can’t become a viable alternative to the ruling party, because they are afraid to talk about their own differences – out of fear that it would serve the government’s interests. Moving forward, the crisis brewing within the CHP, the opposition’s flagship, will put other opposition parties in a difficult situation as well.

[Daily Sabah, February 2, 2021]

In this article

- Opinion

- Anti-Erdoğanizm

- Augmented Parliamentary System

- Daily Sabah

- Fight Against Terror

- Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu

- Kurdish Community

- Kurdish Question

- Opposition

- Özgür Özel

- People's Alliance

- Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

- Türkiye's Good Party (IP)

- Türkiye's Justice and Development Party | AK Party (AK Parti)

- Türkiye's Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP)

- Türkiye's Republican People's Party (CHP)

- Türkiye's Republican People’s Party (CHP) Chairperson