Edward Said, in his monumental work “Orientalism,” problematizes the West’s identification with “rationalism, individualism, and material advancement” and the East’s “religion and tradition.” In much of his works, Said criticizes the way the West has constructed itself by moving off of the negative features associated with the East and thus legitimizing its hegemony over the world.

Despite all of Said’s criticisms, the current de facto situation has not changed. Even today, mainstream Western academia and media speak from within the orientalist perspective it has been rooted in since the 19th century by looking at its own “East.”

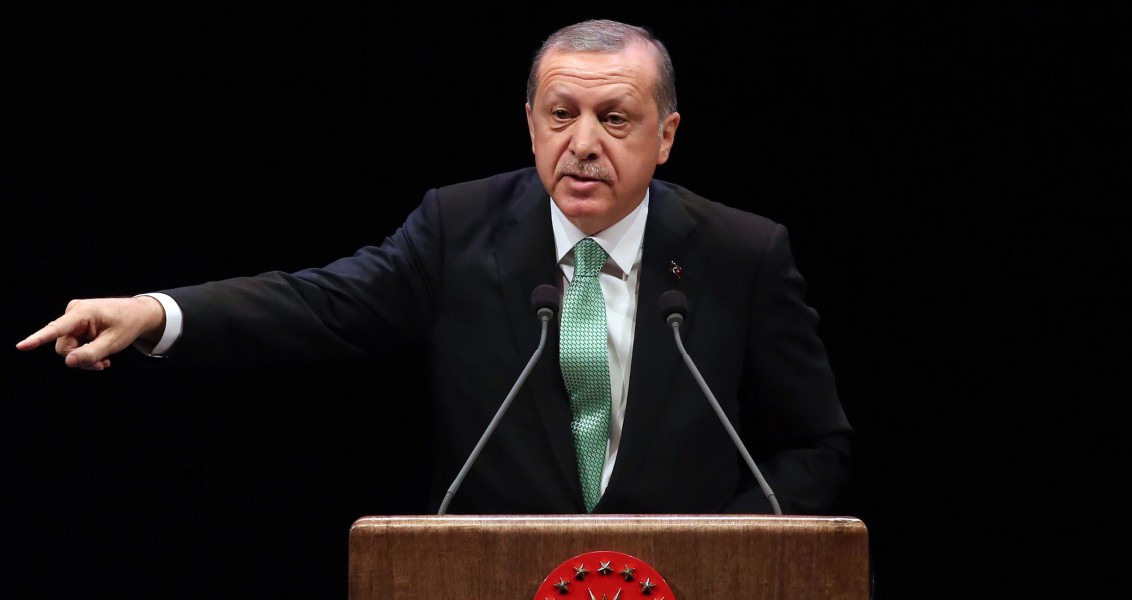

Unfortunately, the analyses done on Turkey also contain a portion of this viewpoint. This perspective, which has been fed and grown in the media and academia, is reflected in popular culture and the world of politics. At the point we have arrived at, the Republic of Turkey is regarded as a country that has been “unable to Westernize,” that actually “resists Westernization.” According to this perspective, although Turkey took steps toward Westernization under the direction of a pro-Westernization and modernization elite before the 2000s, after the 2000s, it has “become Eastern” with the arrival of the “religiously oriented” Justice and Development Party (AK Party) to the administration.

Again according to this perspective, Turkey had taken important steps within an “institutional and ideological” framework toward Westernization until the 2000s, but was unable to carry this period to the level of the “masses.” The allegation has been that with the AK Party administration, the “institutional and mental/ideological” framework of the politics of Westernization that had been applied for decades had begun to be harmed and what was instead carried to the masses was “anti-Westernism.”

Samuel Huntington, in qualifying Turkey as a “torn country,” reflects the mainstream perception of Turkey in Western academia and media before the 2000s. According to him, Turkey is a country between the “Islamic world” and the “West.” But the essential cause behind Huntington’s “torn country” qualification is not this. According to him, Turkey is divided between the “elites” who perceive themselves as Western and the people who regard themselves as “Eastern and Muslim.”

As will be seen in many of the arguments over “Turkey’s identity” in the West, we are also faced here with an explanatory framework that puts the “secular-religious” distinction at the center. In fact, sociologists who joined Turkey’s identity debates from within the paradigm of Westernization chose to evaluate Turkey’s modernization as “secularization” and took the “secular government-religious people” dichotomy as its base.

However, this separation was not often evaluated as being problematic. Quite the opposite, Turkey was shown as a “model country” that could be exported to the Middle East as a country with a Muslim population and a secular government. However, the radical secular politics that were applied in Turkey turned, in the long-term, to be part of Turkey’s “identity crisis.”

There is no longer a physical base for qualifying Turkey as a “torn country” after 2000. The contrast between the government and the people began to be removed through the AK Party’s policies. Secondly, the new dynamism in foreign policy embraced by Turkey in its assertion to be a regional power distanced it from the perception of a “country caught between the Islamic world and the West.”

All the same, Turkey’s choice of “plural modernization” was regarded as an “Easternization syndrome” by the West. Turkey, which had been viewed as an “exemplary country,” came to be otherized. Turkey today is unfortunately in the position of being the foremost other of the Western world. This is a speculative reality. The orientalist roots of the Western world’s attempt to construct its own identity over Turkey are clearly displayed.

Westerners need to consider Turkey’s place in international politics from a realistic, not imaginary, perspective and to evaluate it from strategic, not historical, priorities. Possibly the lack of foresight with regards to Turkey’s politics and the continual use of bad strategies for the past 15 years could be their “cultural prejudices.” When they have gotten rid of their “cultural prejudices,” they will see the naked truth that is the “Turkish model of the imperial West” has collapsed and that Turkey has constructed “its own humble but well-established model.”

[Daily Sabah, November 4, 2016]